City Park Pool

“You can’t tell the story of history just by leaving out certain things you don’t want them to know or see. You can’t do that. You can’t tell part of the truth. You have to tell the whole truth. You have to show it to them so that they do understand. And that is our responsibility.”

– Ruby Bridges, 2021

In the summer of 1943, there was one public pool in the city of Baton Rouge – City Park Pool – and legally, only white people were allowed to swim in it.

Jim Crow laws ruled the south during the century following the abolishment of slavery and these set of statutes – named after a black minstrel show character and not a real person – restricted the civil rights of an entire race of people because of the color of their skin. They were denied education, voting rights, seats on a bus. They were banned from certain restaurants and job opportunities, forced to use separate public restrooms and drink from separate water fountains. They were denied access to City Park Pool.

But human beings – especially teenage boys with a penchant for adventure – who have been banned from swimming in a pool, find other sources of water.

While laws are laws, kids are kids.

And hot is hot.

Summertime in Baton Rouge is brutal. The humidity is often so thick, it feels like it’s suffocating to walk outside for more than five minutes. Time slows down, work days are shorter and cool water is a necessity. Because segregation denied access to the public swimming pool, many found relief in lakes, creeks and flooded areas around town.

In the summer of 1943, three young black teenagers drowned in different watering holes around Baton Rouge. Rev. Willie K. Brooks was a scout leader and a church leader, and he knew the boys’ families. Their losses affected him and it affected many families living in the predominantly black neighborhood in Old South Baton Rouge.

In times of need, leaders do what leaders often do, when something needs to be done.

They lead.

According to the 2008 LPB documentary, “Baton Rouge’s Troubled Waters,” Brooks wanted to find a safe alternative to dangerous water. He wanted there to be a pool for black families and their children to swim in safely. He found some land, organized the United Negro Recreation Association, fundraised and persisted.

While City Park Pool was funded by city taxes, the pool that Brooks wanted to build was funded by private donations, concerts and plate lunches. Local, courageous leaders stepped up to help, even those who were vocal about the injustice of people who pay taxes, having to pay for their own swimming pool.

Marion Wells, a white woman who served as the executive director of Blundon Orphanage, a home for black orphans, donated space for the UNRA to meet. And while the city eventually supported building the pool, I did not find any evidence that it provided any financial assistance.

My idea to write about City Park Pool started when I watched “Baton Rouge’s Troubled Waters.” The hour-long piece opened my eyes to an issue I didn’t even know about. I took my kids to City-Brooks Community Park often when they were little. We climbed the jungle gym, I pushed them on the swings, but I never paused to find out about the land I was standing on or learn about the name of the park.

I was intrigued by Brooks and his tenacity so I decided to dig deeper into the historical timeline of City Park Pool. I researched old newspaper articles and found that the narrative was different. The Advocate articles didn’t mention the teens’ drowning or the segregated pools when reporting on Brooks’ plan. But one article said there was a need for a pool and recreational center to combat the “severe wave of juvenile delinquency.” According to the July 12, 1945, issue of the Morning Advocate article, “Meeting on Negro Recreation Unit Set:”

“Plans for erecting a swimming pool and recreational center for negro patrons will be discussed at a meeting of the United Negro Recreational Association of East Baton Rouge Parish, called for Monday night at 8 o’clock at the negro USO, Napoleon and Terrace streets. Several months ago, under the leadership of W.K. Brooks, the association was organized for the specific purpose of aiding the city authorities in combatting the present severe wave of juvenile delinquency by motivating all civic forces to rally and support this recreational project. Brooks said that to successfully prosecute this project, wholesome recreational facilities must be provided, and it is generally conceded that a swimming pool and recreational center will prove most effective. Naturally, he added, funds must be raised to bring about this realization, and in this connection, a ‘financial drive’ will be launched shortly. All members and team captains are urgently requested to be present at the meeting to receive literature and final instructions. All other public-spirited citizens are invited to be present. This project has the endorsement of city authorities.”

The documentary I watched never mentioned any juvenile delinquency issues. This specific article did not cite any statistics or specific events, and I could not find any other articles in The Morning Advocate supporting the increase in juvenile crime. These two completely different narratives left me wondering if Brooks felt like the project wouldn’t happen without the green light from the city? And in order to get the city’s approval, did he have to change the story to fit the city’s agenda? Or was it simply a syntax issue? Were the boys, who drowned, trespassing on the waters where they lost their lives? Was the article meant to elicit and squash fear in the white community, ultimately gaining their support? Why did taxes support City Park Pool but the UNRA had to raise money to build a pool for black people? I was confused by the two different stories surrounding City Park Pool. But at least I had all of the information — that I could find — in front of me.

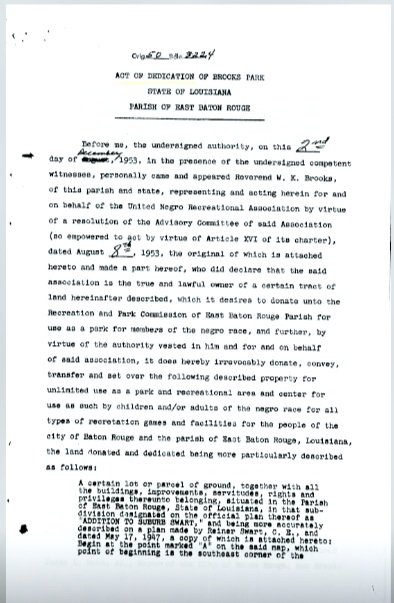

It took Brooks and the UNRA years to build a pool and a playground, but they did it. In May 1947, they bought four acres of land — across from a cemetery — for $16,000 near the former McKinley High School on the corner of Pear Street and Eddie Robinson Sr. Drive. They raised $60,000 and Brooks Park Pool was dedicated in 1949, six years after the three young boys drowned.

In the 1950s, Brooks Park Swimming Pool was the place to be in the Old South Baton Rouge neighborhood. There was a parade for its grand opening. The entrance fee was $.25, and in its early days, the pool had to open in shifts because so many people wanted to swim. Brooks accomplished his goal – to create a safe place for black children and families to swim. In 1953, the UNRA donated the Brooks Park Pool to the Baton Rouge Recreation and Parks Committee or BREC, as we call it today. The contract stated that the land would always be used as a park for the surrounding population or it would returned to the UNRA.

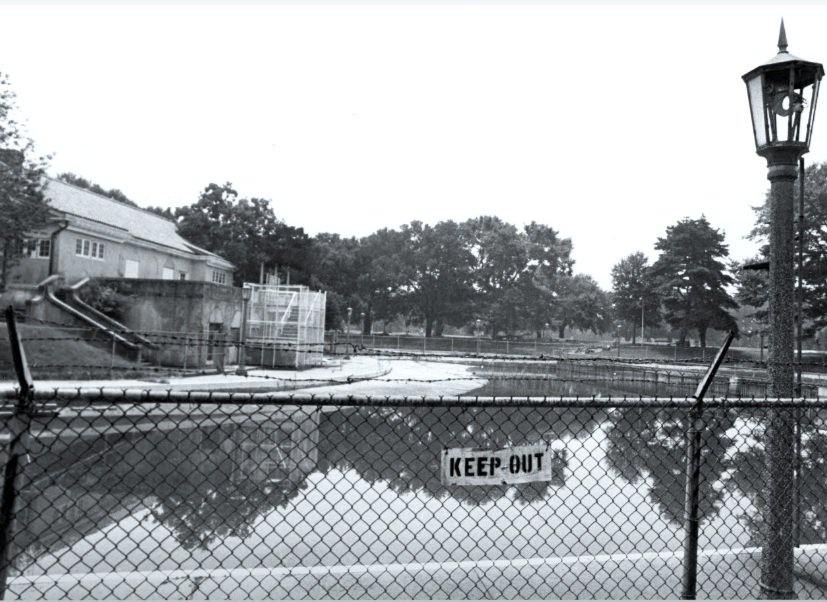

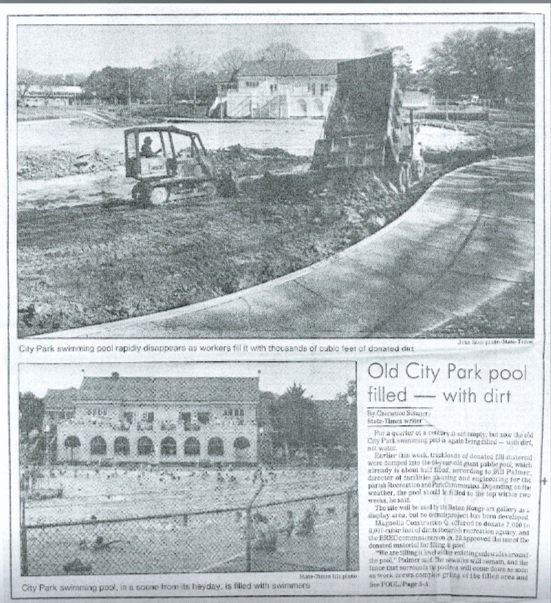

While Brooks Park Pool is open today as a smaller pool, City Park Pool closed in the early 1960s. City leaders blamed financial issues and a rash of drownings for the reason for its closure.

That’s one narrative.

But the Civil Rights Movement and changing national legislation sparks the other narrative.

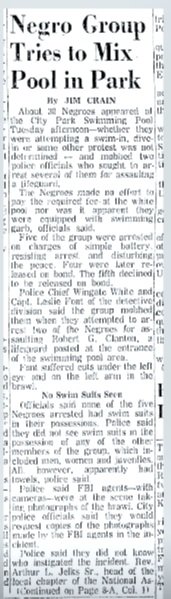

On Tuesday, July 23, 1963, a group of 30 black men and women demanded entrance to City Pool Park as part of a “swim-in,” according to an article in the Capital City Press. Five activists were arrested on charges of simple battery, resisting arrest and disturbing the peace, including Pearl George (who would later be the first black woman on the Baton Rouge Metro Council) and her sister Betty Claiborne. (In 2005, Pearl and Betty were pardoned of all charges by Gov. Kathleen Blanco).

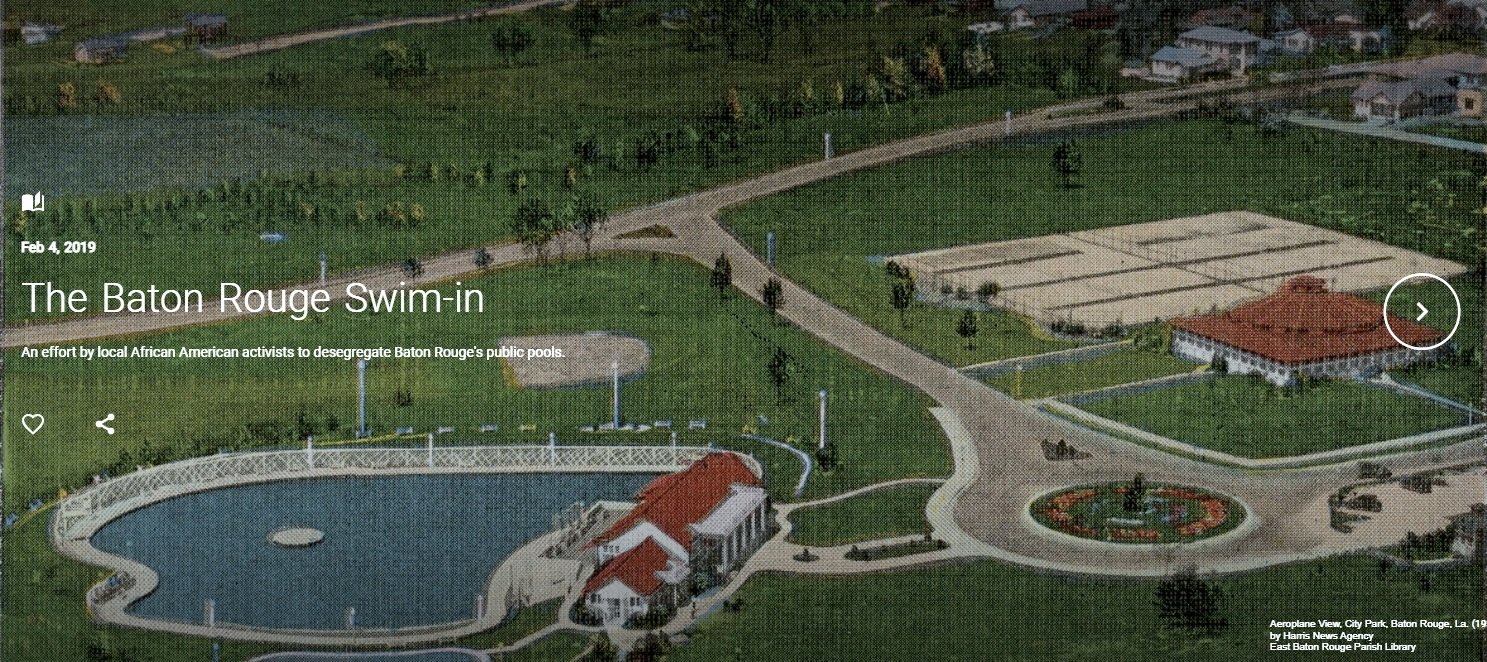

According to East Baton Rouge Public Library’s Exhibit, “The Baton Rouge Swim-in: An Effort by Local African American Activists to Desegregate Baton Rouge Public Pools,” the Baton Rouge Recreation and Parks Commission closed all public pools indefinitely in May 1964, two days before a local ruling came down that would end segregation in all public park facilities.

City Park is now called City-Brooks Community Park, a nod to Willie K. Brooks and his dedication and tenacity in opening a pool for the neighborhood. It spans each side of Dalrymple Drive. There’s a path connecting City Park to Brooks Park Swimming Pool and playground, an uphill paved .6 mile-stretch for bikes and pedestrians and the occasional scooter.

The site of City Park Pool is located on the Tennis Court and Golf Course side of Dalrymple Drive. It’s behind the Baton Rouge Gallery, once the pool house and snack bar. A short walk down a few stairs leads you to the bowl-shaped area that used to be a lagoon-style pool. All that’s left from then are a few light poles. They surround a large, manicured, grassy area and a small splash pad, anchored by a long concrete bench.

I brought my family here last month. My kids and husband navigated the nearby labyrinth as I sat on this bench on a breezy and chilly Monday afternoon, looking at the grass and the back of the gallery, trying to think about what it would have felt like to be denied access to this pool. I thought about Brooks and how his dream of providing a safe place for kids to swim probably saved a lot of lives. I’m sad that City Park Pool closed before it was integrated. But less than one mile away, Brooks Park Swimming Pool remains open. It’s smaller now, and while it’s mainly used by kids from the neighborhood, it’s also used by BREC campers from all of the city. My son swam there last summer.

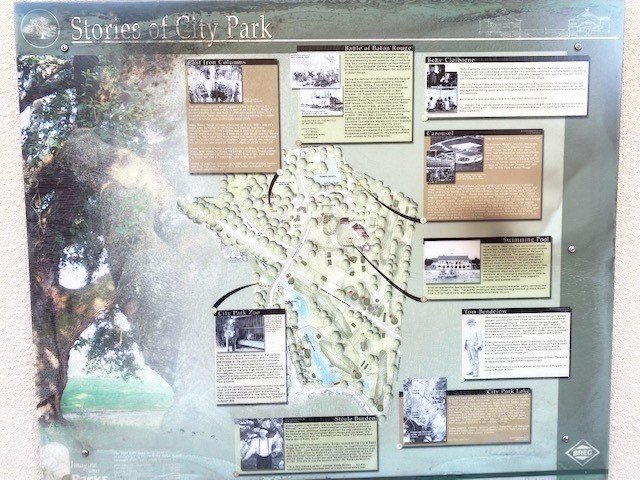

On the way back to our car, we stopped at one of the cast iron columns that denotes a piece of history about City-Brooks Community Park. The column sits on top of a stone base and is one of 12 that supported the old Baton Rouge City Market from 1859 and the original Picnic Hill Pavilion, built in 1955. Copper bowl luminaries sit on top of the tall columns, sometimes called braziers, and plaques with historical information are bolted to the base of the columns.

There’s a picture of the swimming pool on one of the plaques with the date it was built – 1930. A group of beach-cruiser style bicycles, popular in the 1940s and 50s, are in the forefront of the photo, while a group of white people are in the pool in the background. The caption reads: “The large lagoon shaped City Park swimming pool saw its golden age in the 1940’s and 1950’s.”

It’s hard not to feel nostalgic about everything this photo represents – the carefree days of summer, riding your bike to the local pool and spending all day with your friends. But it’s not the whole story of City Park Pool, and I’m quickly reminded of a quote I once heard by author Jon Meacham about the “narcotics of nostalgia.”

He says, “We can’t hang a lantern on what we want to remember. We are better off when we include, not exclude.”

I wanted to see if BREC included the whole story on the park’s property. At the bottom of the plaque, there was information pointing us to the Tennis Center for more historical information.

When we walked across the parking lot to the Tennis Center, there was a larger plaque bolted to the wall across from the Tennis Shop. The title read, “Stories of City Park.” I scanned the plaque until I found the story of the Swimming Pool. There was a picture of the old pool house. There was no mention of denying black people entrance to the pool, but the last sentence said this: “After several deaths due to drowning, as well as overcrowding, and other safety concerns, the pool was closed in 1964. The painful challenges that racial issues presented at this turbulent time in American history, also contributed to its ultimate closure.”

After all of my research, I wanted more information about the injustice of the pool to be presented to the general public, but I was happy that at least BREC included some information. I stood there, wondering if history would have been different if a few prominent families stood up during the 1940s or 1950s and said it was wrong to exclude people because of what they looked like. Would they have been socially ousted by family and friends? Would their kids have been bullied? Would their jobs have been in jeopardy? Their lives threatened? Or would others have followed? I wonder what it felt like to be on either side of that fence.

We left City-Brooks Community Park and drove to Brooks Park Swimming Pool on Eddie Robinson Sr. Drive. It’s a 12-minute walk, a two-minute drive.

The Old South Baton Rouge neighborhood is now a ghost town of what it once was. This close-knit, economically stable black community is nightly news fodder for violent killings. Dilapidated homes and businesses now line the city streets. And in 1960, construction of the interstate splintered this once thriving community. But the pool, across from the cemetery, next to the school, remains.

Brooks Park Swimming Pool is a constant reminder of leadership at its best and the beauty of neighbors who worked together to create a better life for their children.

Thank you to LPB and the East Baton Rouge Parish Library.

February 18, 2022